I often associate the books I’ve edited and loved strongly with the place where I first read the manuscripts. I finished the first draft of Millicent Min, Girl Genius in the lounge of LaGuardia Airport, as I waited for my family to arrive from Kansas City for their first-ever trip to New York. I read the first two chapters of the book that would become A Curse Dark as Gold in my beloved yellow wing chair by the window of my old apartment, and completed the full manuscript in my beloved blue sling chair in the corner of my old office. I inhaled all of Sara Lewis Holmes’s Operation Yes in two long sessions in the Scholastic Library, in the comfortable armchairs overlooking Broadway, then went back upstairs and told our assistant Emily that I wanted to acquire it.

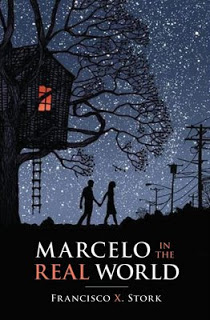

I often associate the books I’ve edited and loved strongly with the place where I first read the manuscripts. I finished the first draft of Millicent Min, Girl Genius in the lounge of LaGuardia Airport, as I waited for my family to arrive from Kansas City for their first-ever trip to New York. I read the first two chapters of the book that would become A Curse Dark as Gold in my beloved yellow wing chair by the window of my old apartment, and completed the full manuscript in my beloved blue sling chair in the corner of my old office. I inhaled all of Sara Lewis Holmes’s Operation Yes in two long sessions in the Scholastic Library, in the comfortable armchairs overlooking Broadway, then went back upstairs and told our assistant Emily that I wanted to acquire it.And I read a certain scene late in the manuscript of Marcelo in the Real World on the downtown V train at 53rd St. in Manhattan. I distinctly remember sitting there on the bright orange-and-red plastic seats, the manuscript on my lap, waiting for the train to move after a visit to the Donnell Library, and thinking “Wow. Wow”—that eye-widening, brain-expanding feeling when you’ve read something that changes your view of the world. Marcelo, a young man on the autism spectrum, was talking with a dear friend of his, an adult female rabbi, about religious faith, about suffering, about what we weak and small humans can do to alleviate it; and I had never seen anything like this conversation in YA fiction before (or adult fiction either, for that matter). It wasn’t just the unusual players in this discussion; it was the ambition of it, the way it reached for the Big Questions and caught them. It was the reality and humanity of it—that I could genuinely believe this anguished young man in the button-up shirt and this older woman in the neon-green-framed glasses lived and thought and felt up somewhere near Boston. And it was the way the religious issues chimed within my own heart, my own complex internal stew of Big Questions and small actions and deep longing. I had been impressed by the book before that moment on the V train, but after it—pending the author being open to revisions, and not a jerk—I wanted to acquire and edit the manuscript desperately.

So I called the agent, Faye Bender, who arranged a phone call for me with the author, Francisco X. Stork. These conversations are always a little nervous and hesitant—like a first date, both of us auditioning for the other; but he was lovely to talk to: clearly open to revisions, and not a jerk. I took the manuscript to Arthur and the rest of the people in our Acquisitions process, who responded with equal enthusiasm; I made an offer to Faye, and with a little back and forth, Marcelo was mine.

And just as I had never read a manuscript like Marcelo before, I edited it in a manner that felt different from anything I’d done before. A quick plot summary:

Marcelo Sandoval hears music that nobody else can hear – part of an autism-like condition that no doctor has been able to identify. But his father has never fully believed in the music or Marcelo's differences, and he challenges Marcelo to work in the mailroom of his law firm for the summer…to join "the real world." There Marcelo meets Jasmine, his beautiful and surprising coworker, and Wendell, the son of another partner in the firm. He learns about competition and jealousy, anger and desire. But it's a picture he finds in a file – a picture of a girl with half a face – that truly connects him with the real world: its suffering, its injustice, and what he can do to fight.There are four intertwined plotlines here: Marcelo’s relationship with his father, which kicks off the action; his relationship with Jasmine, which provides much of the book’s warmth; his relationship with Wendell, which provides many of its uglier truths; and what happens when Marcelo finds that picture, which leads to the scene with the rabbi that I mentioned above, and ultimately serves as the thematic heart of the novel. Indeed, there was so much interesting and meaty and true stuff going on in the manuscript that I felt like the first thing we needed to figure out was what was the most important true stuff—identifying the central question the book would ask and then focusing the storyline to provide an answer.

So I decided to try something I'd never done with an author before, and I asked Francisco to write me a letter about the book, how it started for him and what he wanted it to explore and to say. He responded with a three-page essay that showed both his ambition, in articulating a hero’s journey for Marcelo, and his compassion, in identifying the thematic ends that journey would serve. The central question was how a holy person—someone with his mind on things not of this world, as Marcelo is—would react to things of this world bursting in on him: suffering, injustice, betrayal, love. What was the right action in response to those things? Was it possible—perhaps even desirable—to stay away from them, in that higher removed plane? Or must they be confronted, and if so, what were the risks and costs? These questions struck me as not just spiritual concerns, but profoundly YA ones, as teenagers are often for the first time facing departure from their own safe spaces, the fallibility of their idols, and the costs of their choices.

And Francisco’s essay became our touchstone throughout the months-long editing process, as we used his answers to shape and strengthen the plot, particularly in distributing the screen time for those four intertwined plotlines. We worked on making the stakes clear at the outset and then raising them throughout the book, as Marcelo’s ability to negotiate “the real world” developed and his relationships with Arturo, Jasmine, Wendell, and the girl in the picture intensified. My beloved bookmaps helped us monitor the pacing, so that the various revelations of Marcelo’s journey each resonated within the action and were given adequate processing time in his mind. And when it came to the line-editing, having the essay’s larger statement of purpose reminded detail-obsessed me to keep my eyes on that purpose, making sure the edits I suggested contributed to our overall aims.

Despite all this, there was a fair amount of trial and error on both sides. . . . I’d suggest a new scene arrangement to Francisco that I’d then rearrange again in the next draft (which I’m sure was great fun for him), and he estimates that in the end he rewrote half the book, which sounds about right. But both of us were drawn on by our desire to do justice to the questions he raised and the people he created, to bring as much fullness of truth to the story as we could. The novel provided its own metaphor for this search for truth: Jasmine is a composer, and she tells Marcelo at one point, “The right note sounds right, and the wrong note sounds wrong.” Thanks to Francisco’s marvelous gifts and hard work, Marcelo in the end is full of right notes.

And I’m not the only one who thinks so; the novel has received five starred reviews and much high praise elsewhere, including this great notice in Ypulse and this from the Cleveland Plain-Dealer. Francisco was featured in the Boston Globe this past weekend and also in a Publishers Weekly Q&A conducted by my friend Donna (whose class at Boston University Francisco and I visited back in October). Marcelo is what I think of as a “Book of my Heart,” one that still makes me say “Wow. Wow” when I revisit it today; and if you have the chance to read it, I hope it moves you too.