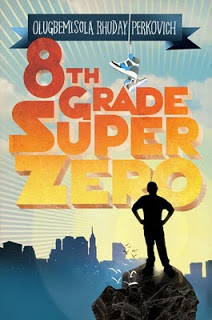

In May of 2006, a writer named Olugbemisola Rhuday-Perkovich sent me a query letter for a novel then called Long Time No Me. After several reads and a noncontractual revision, I acquired the book in December of 2007; and two years and a month later, that novel is now in stores as Eighth Grade Superzero -- praised as a "masterful debut" in a starred review from Publishers Weekly.

In May of 2006, a writer named Olugbemisola Rhuday-Perkovich sent me a query letter for a novel then called Long Time No Me. After several reads and a noncontractual revision, I acquired the book in December of 2007; and two years and a month later, that novel is now in stores as Eighth Grade Superzero -- praised as a "masterful debut" in a starred review from Publishers Weekly.Gbemi has kindly allowed me to reprint her original letter here and annotate it as a companion to the Annotated Query Letter from Hell; I think of this as the Annotated Query Letter That Does It Right. Much of what it Does Right is that it speaks so specifically to me and my tastes, as you’ll see—my interest in writers of color and in racial, religious, and other moral questions—and clearly those tastes would not be applicable to all acquisitions editors. But if you can divine from an editor’s books, blog posts, talks at conferences, or other material what his or her tastes are, then this might hint at ways to tailor your description of your novel to fit those tastes. And if you have no idea about an editor’s tastes, this is still a useful example for its professionalism, efficiency, thoroughness, and overall grace. The numbers in parentheses are my annotations.

May 31, 2006

(1) Cheryl Klein

Arthur A. Levine Books

557 Broadway

New York, NY 10012

(2) Dear Ms. Klein:

(3) We met at the Rutgers University Council on Children’s Literature (RUCCL) One-on-One Plus Conference last October, and (4) I’ve since enjoyed your words on moral dilemmas and character values, as well as some of the books you’ve worked on. (5) I loved Lisa Yee’s painfully funny Millicent Min, Girl Genius, and Saxton Freymann’s Food for Thought has been a crafting inspiration as well as a teaching aid.

(6) In my middle-grade novel Long Time No Me, (7) Reginald “Pukey” McKnight created a superhero character in kindergarten; (8) now secretly dreams of being a real-life hero. (9) The Guy who’s got game and gets the Girl. Instead, he threw up on the first day of school. In the middle of the cafeteria. In front of everyone. 8th grade has gone downhill ever since.

(10) Now Reggie can’t even look The Girl in the eye, and his former best friend is bent on shredding his already tattered reputation. Sometimes he thinks it would be best to just exist between the lines and slide under the school’s social radar. (11) That won’t be easy when Reggie’s current best friend is white, a fact that seems to matter more and more, and his oldest friend is bent on “speaking truth to power” to anyone and everyone. (12) Reggie wonders why things are so bad if God is so good; his faith at all levels is challenged by (13) his father’s unemployment, his encounters with a homeless man, and his role as a “Big Buddy” to a younger version of himself. (14) When he finally decides to “be the change he wants to see” and run for school President, Reggie learns that sometimes winning big means living small.

(15) I’ve been published in national teen publications such as Rap Masters, Word Up, and Right On, and developed teen-oriented projects for clients including Queen Latifah, Girls, Inc., and Sunburst Communications. (16) I focused on my writing for children in workshops with Madeleine L’Engle and Paula Danziger, and was a three-time mentee at the RUCCL One-on-One Plus Conference. The Echoing Green Foundation twice awarded me a public service fellowship for my work with adolescent girls. I received my M.A. from New York University in Educational Communication and Technology with a concentration in Adolescent Literacy, and my B.Sc. from Cornell University in Print Communication. (17) I am a member of the Society of Children’s Book Writers and Illustrators (SCBWI).

(18) Would you like to see sample chapters of Long Time No Me? An SASE is enclosed. I can be contacted at [phone number redacted] and by email at [email address redacted]. Thank you for your time and consideration.

Sincerely,

Olugbemisola Rhuday-Perkovich

(1) & (2) In the spirit of contrasting this with the Query Letter from Hell, it’s worth pointing out: She spells my name and gets my publishing house right, and refers to me as “Ms. Klein,” as is proper in business correspondence. I would call her “Ms. Rhuday-Perkovich” in turn.

(3) She identifies where we met, at the One-on-One Conference seven months previously. Even if I don’t remember an attendee specifically (which I often don’t, I confess, given that I attend three to six conferences a year), a line like this is useful in establishing that this isn’t a query out of the blue: The writer has heard me speak and knows something about me, my editorial values, and likely what I’m looking for, which increases the odds that this is a thoughtful query I will like, as opposed to a query-bomb directed to ten editors plucked at random from the Children’s Writer's and Illustrator's Market.

(4) She mentions material posted on my website or blog. I always appreciate small compliments like these, particularly when they show that the writer values the same things I value—in this case, moral dilemmas and characters with depth. However, I would caution writers not to place too much emphasis or spend too much time on these sorts of personal compliments to editors with blogs or websites or what have you: We judge a query on the description of the book and the strength of your writing, not how nice you are to us.

(5) She brings up two of the books I’ve edited, which again indicates that she knows something about me and what I like; and she adds comments that show she has read and really “got” the books, not just picked them out of my list of books I edited. I especially love her description of Millicent Min as “painfully funny,” because that’s exactly what that book is—a perfect little fugue of awkwardness and hilarity—and the fact that Ms. Rhuday-Perkovich (as I thought of her then) recognized and praised the pain in it, not just the funny, made me sit up and take notice of her own work.

(6) She identifies upfront what genre her novel is. This is extremely useful as picture books have to be judged by a different standard than middle-grade novels, and ditto for middle-grade vs. YA, or all of them vs. nonfiction or poetry; and an early-in-the-letter identification of the genre helps me move my brain into the standards of that particular form.

(7) The name “Reginald McKnight” would have signaled to me that this was likely a novel about a young Black man (as that first name and surname are most common in the Black community in the U.S.), and this also would have been a point in the manuscript’s favor, as I’d like to publish more books about and by people of color.

(8) Yes, there is a subject missing here after the semicolon, and I point this out only to say that I requested the manuscript anyway—that the writer and character and book all sounded interesting enough to outweigh the “mustard on the shirt” (in Query Letter from Hell terms) of a minor grammatical error.

(9) “The Guy who’s got game and gets the Girl. . . . In the middle of the cafeteria. In front of everyone.” Coming out of this description, I sympathized with Reggie not just because of the grossness of the event—puking in the cafeteria in front of everyone! Ugh, poor guy—but because I got a glimpse of him in the language. These little details of capitalization and rhythm hint at the manuscript’s voice, and that it’s a distinctive voice, not a voice I’ve seen in many other query letters and manuscripts.

(10) This, the major plot and theme paragraph of the query, says to me that this is a fairly domestic novel, concerned more with local relationships among family and friends than any large-scale external plot to be confronted—which was and is fine with me; my favorite novelist in life is Jane Austen, after all. However, that also means that the characters have to be really well-drawn and well-rounded in order to make readers care as much about the stakes of the characters’ everyday lives as they would about how to defeat the Evil Overlord, say. Here, I’ve already noted that the voice is distinctive, which is a good start, and the rest of this paragraph will bear out the characters’ and relationships’ complexity and depth.

(11) The fact that Reggie’s best friend is white, and that this is remarked upon, confirms my earlier guess that this protagonist is a person of color, and the earlier points in the manuscript’s favor. This next sentence also would have told me that the manuscript delved into racial and political issues, which I find fascinating—all the more so as they often aren’t discussed in middle-grade novels for children; and thus this revealed that Ms. Rhuday-Perkovich wasn’t afraid to tackle big and complex topics in the context of her characters’ lives.

(12) I also love religious questions . . .

(13) . . . and economic issues, so clearly this query is just pushing all my little readerly interest buttons. The reason I love racial, political, religious, and economic questions in books (among many other things, of course) is because we all, even kids, live in a world filled with such questions in real life; and if part of the greatness of art is its fidelity to life, great art, by its realness, must raise such questions. This query letter is saying to me that Reggie and his world and the people in it are all very real.

(14) A very humble, and therefore highly unusual, conclusion to draw; and unusualness + quality realism + ambitious questions + good writing = my interest is piqued.

(15) A biography paragraph in which every fact can be directly connected to (a) Gbemi's knowledge/experience in working directly with children or teenagers, (b) her experience in print communication (which translates as marketing and publicity), or (c) her experience in writing for children. If an author has special expertise related to the subject of his or her novel—if the book deals with a young girl in the world of professional horse racing, say, and the author had been a jockey at Del Mar for two years—then she could also have added (d), her personal knowledge of or experience with the subject; that would have indicated that she was writing from a position of some authority, which is good to know when it comes to an unusual subject or for publicity purposes. In general with queries, any biographical fact that does not fit in categories (a)-(d) should be omitted. Parenthood does not count for (a).

(16) I was especially impressed by the reference to Madeleine L’Engle and Paula Danziger, both of whose fiction I love; and my knowledge of their books and styles told me that most likely Eighth Grade Superzero would have elements of religious inquiry (as the query already demonstrated) and humor, which I would appreciate. (And it does!)

(17) If a writer belongs to SCBWI, that tells me that he or she should be at least somewhat familiar with the submission and publication processes for children’s books, which is very useful in setting expectations on all sides. . . . I can rest assured that the writer won’t be expecting a manuscript submitted in October to be published in book form by Christmas, as in the Query Letter from Hell.

(18) Having made her excellent pitch, Ms. Rhuday-Perkovich exits gracefully, with a direct statement of the letter's implied question—Would you like to see this?—and all relevant information should my answer be yes—which it was! (These days I ask writers to submit two chapters and a synopsis of their novel along with their query letter; this letter was submitted before those guidelines were in place.)

My thanks again to Gbemi for letting me share this letter, and I hope you all enjoy the book it produced.