"A writer needs three things: experience, observation, and imagination, any two of which, at times any one of which, can supply the lack of the others." -- William Faulkner

A writer on my Facebook feed asked a question of his fellow writers recently: How much of writing success is talent, how much perseverance, how much conscious education in craft? I've thought about this a lot as well, so I'm going to ramble on about it for a bit. "Success" we're going to define here as "The ability to achieve the ends you want to achieve aesthetically for both yourself and a reader"; the elements of publishing/sales success are related, but much less in the writer's control.

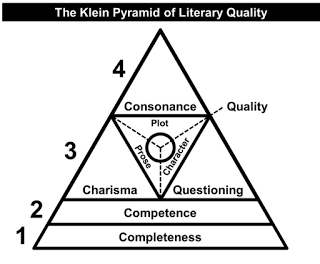

First, talent. I actually don't think "talent" as a term is very useful, because what we mean when we talk about "talent" breaks down into a number of constituent elements that are more interesting and helpful to discuss. To wit, I believe "talent" is actually a combination of:

Imagination: The writer is capable of envisioning and creating on paper something new on this earth: a new human being, a new form of magic, a new planet, a new story. Of course this is what most writers do, but writers who are gifted in imagination take that a step beyond, to put together things no one else has thought to join before, and then render those inventions thrillingly real and meaningful: Ursula K. LeGuin with the genderless world of The Left Hand of Darkness, or Shaun Tan's faceless exterminators in one of the nightmare worlds of The Arrival, or Neil Gaiman relocating gods from all around the world to the United States in American Gods, or J. K. Rowling's conception of wands as indicators of personality. Or these gifted writers demonstrate great depth and breadth in what they imagine.... Half of Americanah, by Chimimanda Ngozi Adichie, is set in a cramped, fluorescent-lit African hair-braiding shop shown in such well-chosen detail that readers can scent the oils in the air. Or Patrick O'Brian created Stephen Maturin, a short, half-Irish, half-Catalan doctor, naturalist, spy, violin player, Catholic, opium addict, faithful lover, terrible husband, worse housekeeper, excellent friend, awful seaman, who is more real to me than half of my acquaintance, because Mr. O'Brian imagined him that deeply and wonderfully. An original imagination, as with Ms. LeGuin or Mr. Gaiman, will attract readers for the chance to expand our minds beyond the familiar; a deep imagination, as with Ms. Adichie or Mr. O'Brian, will attract readers for the chance to delve farther into what we already know is real. Either way, they offer the pleasure of discovery to readers, who then feel they can confidently come to this writer to see something new.

Observational Skill, leading to Emotional and Philosophical Insight: The writers whom I admire most are ones who are capable of creating human beings whom I believe in as real people, and then using those characters to say something true and maybe new about the real world that is all around us. That requires these writers (1) to have observed human beings carefully, and remembered and thought about what they observed, so they could combine those thoughts with their imaginations, and create characters with the histories and personalities and all-around richness of real people. (That in turn requires writers to have an interest in human beings to start with, and the skill and patience to observe and remember and analyze. Not all people have those qualities.) And (2) the writers must have something to say about our world -- about race, or death, or politics, or war, or how love feels, or the pleasure of hating something. Some of this wisdom can come about through observation, but a lot more arrives via life experience -- especially pain, if you can use it well.

Dramatic Skill: The ability to make observed or imagined creations join together and move on the page in some emotionally compelling action. This usually involves a sense of timing on the writer's part -- knowing just how long to let the lovers stare into each others' faces before a kiss, or how to make a fight scene move at the proper speed. And it involves a sense of what is dramatically compelling to other people: Not just that you have two men sitting on a stage for hours, but giving them something to do or to talk about, even if it's the fact that they aren't going anywhere.

Writing Craft: The ability to put the results of all this imagination and insight down on the page in a manner that clearly communicates those thoughts and feelings to a reader. That simple, and that hard.

All of these things could be inborn, or they could germinate through the years before the writer starts to write, in combination with one other element that isn't exactly talent, but is absolutely essential to a writer's development:

Unconscious Reading: Thirty percent of writing well is getting good prose and story structures into your bloodstream -- or maybe forty or fifty percent, I don't know. The younger you start, the better; the more you read, the better. (I often read submissions with prose that I find just not very good, and I think "This writer hasn't read enough good prose" -- the Writing Craft part of their talent just isn't there yet.) Your reading forms your sense of sentence structure: I spent ages 13-21 more or less living in Jane Austen novels, and as a result of the way her work blossomed in my brain, I am close to incapable of writing a sentence with simple structure and fewer than five words. Your reading also defines your vocabulary, which in turn defines the store of words available to you to convey whatever you want to say. The content of what you read then determines what defines a good story for you -- whether it's giant wham-pow fights or witty banter or two characters having long philosophical dialogues. That often becomes the kind of story you will end up writing in fiction, because that is what makes you happy as a reader. Or it becomes what you react against, as you see a story created by someone else, and you want to tell it your way, or just better.

Your reading combines with all of the elements of talent identified above, especially dramatic skill and writing craft, to form the base level at which you work, the moment you decide to sit down in front of a blank page. And then you have to:

Practice: So. Much. Practice. "I know what I think when I see what I say," E. M. Forster said, and a writer's unique personality and the range of their abilities can emerge only through doing a lot of saying -- writing, and writing, and writing, and then revising, revising, revising. Practice is the only thing that can help you close the Taste Gap, as Ira Glass calls it: "Do a huge volume of work." It helps you develop confidence, as you see what you're good at and figure out how to fix the issues that come up in the Taste Gap. That confidence then frees you up to take risks and try new things. It doesn't matter how much talent you have, if all the skill and wisdom and imagination of Jhumpa Lahiri and Katherine Paterson and Ray Bradbury flows in your veins: You will never become a good writer without practice and then more practice.

Let's say you have talent and you're practicing regularly in order to get better. The following things can then help you improve and/or increase your odds of writerly success as well:

Conscious Reading: Separate from the Unconscious Reading above: This is the reading you do to study the techniques other writers use to achieve their effects. You can then imitate or steal those effects for your own ends. When I wrote "So. Much. Practice." above, I was stealing an effect I have seen in many, many places -- mostly online, but I think it's shown up in printed work as well -- where those ultra-short sentences (hey, fewer than five words!) give the point about the necessity of practice extra weight by virtue of their brevity. Studying books about writing and storycraft (like my own Second Sight) would also fall into this category.

Cultivating a Process: Write longhand first, then dictate that writing into a computer. Type 50,000 words in thirty days. Create a detailed outline of each scene and plot point, then flesh it out in prose. Be Anthony freaking Trollope and write precisely 250 words every fifteen minutes from 5:30 to 8:30 in the morning. Post all your writing on the Internet and get feedback from anonymous commenters. Never let any civilians see a word until your editor has reviewed the entire novel and approved of it. It doesn't matter what you do, and there is no wrong way to do it. Just find a writing and revising process that helps you do your best work.

Choosing the Right Material: In the fall of 1815, Jane Austen entered into a correspondence with James Stanier Clarke, a cleric who served as domestic chaplain and librarian to the Prince Regent of England. Mr. Clarke suggested several ideas for possible future novels Miss Austen might write, and she turned them down in a wise letter dated April 1, 1816:

So what is the right material for your personal fictional values and range of practice, your strengths and limitations? What will you enjoy writing, and what are you good at writing? Finding a subject matter and style that brings all of that in line will vastly increase your odds of being successful as a writer -- especially if it's also material that uses the element of talent at which you're strongest to its utmost. (Jane Austen had a deep imagination, but perhaps not a hugely original one; enough dramatic skill to tell the domestic-village stories she wanted to tell, and then observational skill and insight out the wazoo. And then all of her teens and twenties were spent in reading and practice, most of it thoroughly delightful.)

Cultivating a Purpose: Why do you write? This is very useful to know, because it is what will keep you going, especially in finishing something: the need to see a story completed, or get paid, or receive other people's praise, or teach others a lesson, or make some noise, or think out loud. (The latter is mostly why I write, and why I write at such length; once I start getting my thoughts out through my fingers, I feel vaguely unsatisfied until those thoughts are out in full.)

Finding Congenial Sources of Feedback: People who understand what you're trying to do, and can tell you where you succeed and where you're falling short. Essential for course corrections when you lose sight of what you're trying to achieve, feedback for knowing whether you're getting there, and emotional support all around.

If you have talent of some kind and then all of the above working together, then the last thing you need is:

Perseverance: Sheer cussedness, frankly, to stick with the practice and the submissions, the slowness and the unfairness, the damned taste gap and the jealousy, the reviews that don't get it and the reviews that do and then correctly identify the places you failed (which are even worse). The lovely moments in writing are truly lovely, when you nail that thought down in words, when you change a reader's way of thinking and they write to tell you so. You need perseverance to pull you over the many moments in between.

Writers, readers, reviewers: Is there anything I'm missing here? What else do you think is necessary for becoming a great writer?

A writer on my Facebook feed asked a question of his fellow writers recently: How much of writing success is talent, how much perseverance, how much conscious education in craft? I've thought about this a lot as well, so I'm going to ramble on about it for a bit. "Success" we're going to define here as "The ability to achieve the ends you want to achieve aesthetically for both yourself and a reader"; the elements of publishing/sales success are related, but much less in the writer's control.

First, talent. I actually don't think "talent" as a term is very useful, because what we mean when we talk about "talent" breaks down into a number of constituent elements that are more interesting and helpful to discuss. To wit, I believe "talent" is actually a combination of:

Imagination: The writer is capable of envisioning and creating on paper something new on this earth: a new human being, a new form of magic, a new planet, a new story. Of course this is what most writers do, but writers who are gifted in imagination take that a step beyond, to put together things no one else has thought to join before, and then render those inventions thrillingly real and meaningful: Ursula K. LeGuin with the genderless world of The Left Hand of Darkness, or Shaun Tan's faceless exterminators in one of the nightmare worlds of The Arrival, or Neil Gaiman relocating gods from all around the world to the United States in American Gods, or J. K. Rowling's conception of wands as indicators of personality. Or these gifted writers demonstrate great depth and breadth in what they imagine.... Half of Americanah, by Chimimanda Ngozi Adichie, is set in a cramped, fluorescent-lit African hair-braiding shop shown in such well-chosen detail that readers can scent the oils in the air. Or Patrick O'Brian created Stephen Maturin, a short, half-Irish, half-Catalan doctor, naturalist, spy, violin player, Catholic, opium addict, faithful lover, terrible husband, worse housekeeper, excellent friend, awful seaman, who is more real to me than half of my acquaintance, because Mr. O'Brian imagined him that deeply and wonderfully. An original imagination, as with Ms. LeGuin or Mr. Gaiman, will attract readers for the chance to expand our minds beyond the familiar; a deep imagination, as with Ms. Adichie or Mr. O'Brian, will attract readers for the chance to delve farther into what we already know is real. Either way, they offer the pleasure of discovery to readers, who then feel they can confidently come to this writer to see something new.

Observational Skill, leading to Emotional and Philosophical Insight: The writers whom I admire most are ones who are capable of creating human beings whom I believe in as real people, and then using those characters to say something true and maybe new about the real world that is all around us. That requires these writers (1) to have observed human beings carefully, and remembered and thought about what they observed, so they could combine those thoughts with their imaginations, and create characters with the histories and personalities and all-around richness of real people. (That in turn requires writers to have an interest in human beings to start with, and the skill and patience to observe and remember and analyze. Not all people have those qualities.) And (2) the writers must have something to say about our world -- about race, or death, or politics, or war, or how love feels, or the pleasure of hating something. Some of this wisdom can come about through observation, but a lot more arrives via life experience -- especially pain, if you can use it well.

Dramatic Skill: The ability to make observed or imagined creations join together and move on the page in some emotionally compelling action. This usually involves a sense of timing on the writer's part -- knowing just how long to let the lovers stare into each others' faces before a kiss, or how to make a fight scene move at the proper speed. And it involves a sense of what is dramatically compelling to other people: Not just that you have two men sitting on a stage for hours, but giving them something to do or to talk about, even if it's the fact that they aren't going anywhere.

Writing Craft: The ability to put the results of all this imagination and insight down on the page in a manner that clearly communicates those thoughts and feelings to a reader. That simple, and that hard.

All of these things could be inborn, or they could germinate through the years before the writer starts to write, in combination with one other element that isn't exactly talent, but is absolutely essential to a writer's development:

Unconscious Reading: Thirty percent of writing well is getting good prose and story structures into your bloodstream -- or maybe forty or fifty percent, I don't know. The younger you start, the better; the more you read, the better. (I often read submissions with prose that I find just not very good, and I think "This writer hasn't read enough good prose" -- the Writing Craft part of their talent just isn't there yet.) Your reading forms your sense of sentence structure: I spent ages 13-21 more or less living in Jane Austen novels, and as a result of the way her work blossomed in my brain, I am close to incapable of writing a sentence with simple structure and fewer than five words. Your reading also defines your vocabulary, which in turn defines the store of words available to you to convey whatever you want to say. The content of what you read then determines what defines a good story for you -- whether it's giant wham-pow fights or witty banter or two characters having long philosophical dialogues. That often becomes the kind of story you will end up writing in fiction, because that is what makes you happy as a reader. Or it becomes what you react against, as you see a story created by someone else, and you want to tell it your way, or just better.

Your reading combines with all of the elements of talent identified above, especially dramatic skill and writing craft, to form the base level at which you work, the moment you decide to sit down in front of a blank page. And then you have to:

Practice: So. Much. Practice. "I know what I think when I see what I say," E. M. Forster said, and a writer's unique personality and the range of their abilities can emerge only through doing a lot of saying -- writing, and writing, and writing, and then revising, revising, revising. Practice is the only thing that can help you close the Taste Gap, as Ira Glass calls it: "Do a huge volume of work." It helps you develop confidence, as you see what you're good at and figure out how to fix the issues that come up in the Taste Gap. That confidence then frees you up to take risks and try new things. It doesn't matter how much talent you have, if all the skill and wisdom and imagination of Jhumpa Lahiri and Katherine Paterson and Ray Bradbury flows in your veins: You will never become a good writer without practice and then more practice.

Let's say you have talent and you're practicing regularly in order to get better. The following things can then help you improve and/or increase your odds of writerly success as well:

Conscious Reading: Separate from the Unconscious Reading above: This is the reading you do to study the techniques other writers use to achieve their effects. You can then imitate or steal those effects for your own ends. When I wrote "So. Much. Practice." above, I was stealing an effect I have seen in many, many places -- mostly online, but I think it's shown up in printed work as well -- where those ultra-short sentences (hey, fewer than five words!) give the point about the necessity of practice extra weight by virtue of their brevity. Studying books about writing and storycraft (like my own Second Sight) would also fall into this category.

Cultivating a Process: Write longhand first, then dictate that writing into a computer. Type 50,000 words in thirty days. Create a detailed outline of each scene and plot point, then flesh it out in prose. Be Anthony freaking Trollope and write precisely 250 words every fifteen minutes from 5:30 to 8:30 in the morning. Post all your writing on the Internet and get feedback from anonymous commenters. Never let any civilians see a word until your editor has reviewed the entire novel and approved of it. It doesn't matter what you do, and there is no wrong way to do it. Just find a writing and revising process that helps you do your best work.

Choosing the Right Material: In the fall of 1815, Jane Austen entered into a correspondence with James Stanier Clarke, a cleric who served as domestic chaplain and librarian to the Prince Regent of England. Mr. Clarke suggested several ideas for possible future novels Miss Austen might write, and she turned them down in a wise letter dated April 1, 1816:

You are very, very kind in your hints as to the sort of composition which might recommend me at present, and I am fully sensible that an historical romance, founded on the House of Saxe Coburg, might be much more to the purpose of profit or popularity than such pictures of domestic life in country villages as I deal in -- but I could no more write a romance than an epic poem. I could not sit seriously down to write a serious romance under any other motive than to save my life, and if it were indispensable for me to keep it up and never relax into laughing at myself or other people, I am sure I should be hung before I had finished the first chapter. No, I must keep to my own style and go on in my own way, and though I may never succeed again in that, I am convinced that I should totally fail in any other.I love this letter partly for the personalities that shine through for both parties -- Mr. Clarke clearly thinking no writer could want anything more in life than to recommend themselves to the Prince Regent; Miss Austen clearly thinking how much he resembles her own Mr. Collins. But I love it more because it is such a wonderful example of writerly common sense and self-knowledge: She knows what her personal fictional strengths and limitations are, and what she enjoys writing in general, and she chooses to work within those boundaries. Or put another way, she knows what her fictional values are -- laughter and real people in country villages, not the highfalutin' pretentiousness of the serious romances of the time -- and she writes within and to satisfy those values. The result is six of the most enjoyable and wise novels in the English language, and I think I speak for most Austen fans in saying we are immensely grateful to have her Persuasion (the novel she wrote after this exchange) in place of any historical romance about the House of Saxe-Coburg.

So what is the right material for your personal fictional values and range of practice, your strengths and limitations? What will you enjoy writing, and what are you good at writing? Finding a subject matter and style that brings all of that in line will vastly increase your odds of being successful as a writer -- especially if it's also material that uses the element of talent at which you're strongest to its utmost. (Jane Austen had a deep imagination, but perhaps not a hugely original one; enough dramatic skill to tell the domestic-village stories she wanted to tell, and then observational skill and insight out the wazoo. And then all of her teens and twenties were spent in reading and practice, most of it thoroughly delightful.)

Cultivating a Purpose: Why do you write? This is very useful to know, because it is what will keep you going, especially in finishing something: the need to see a story completed, or get paid, or receive other people's praise, or teach others a lesson, or make some noise, or think out loud. (The latter is mostly why I write, and why I write at such length; once I start getting my thoughts out through my fingers, I feel vaguely unsatisfied until those thoughts are out in full.)

Finding Congenial Sources of Feedback: People who understand what you're trying to do, and can tell you where you succeed and where you're falling short. Essential for course corrections when you lose sight of what you're trying to achieve, feedback for knowing whether you're getting there, and emotional support all around.

If you have talent of some kind and then all of the above working together, then the last thing you need is:

Perseverance: Sheer cussedness, frankly, to stick with the practice and the submissions, the slowness and the unfairness, the damned taste gap and the jealousy, the reviews that don't get it and the reviews that do and then correctly identify the places you failed (which are even worse). The lovely moments in writing are truly lovely, when you nail that thought down in words, when you change a reader's way of thinking and they write to tell you so. You need perseverance to pull you over the many moments in between.

Writers, readers, reviewers: Is there anything I'm missing here? What else do you think is necessary for becoming a great writer?