I love reading interviews with other editors and hearing what they have to say about the craft, but for some reason, it only just occurred to me recently that hey, I'm a blogger -- I could do such interviews myself! So here's the first in what I hope will be an occasional series of Q&As on the children's-books-editorial life.

The star today is my good friend Jill Santopolo, who rose from editorial assistant to senior editor at Laura Geringer Books/HarperCollins before becoming the executive editor at Philomel/Penguin last fall. She has also written two terrific middle-grade mysteries starring a young detective named Alec Flint, published by Scholastic Press: The Nina, the Pinta, and the Vanishing Treasure, and The Ransom Note Blues. (And on a personal note, she is just as good a storyteller in person as she is in her books, and if there were any such thing as an editorial Best Dressed List, I have no doubt she would be on it.) Thanks for answering these questions, Jill!

The star today is my good friend Jill Santopolo, who rose from editorial assistant to senior editor at Laura Geringer Books/HarperCollins before becoming the executive editor at Philomel/Penguin last fall. She has also written two terrific middle-grade mysteries starring a young detective named Alec Flint, published by Scholastic Press: The Nina, the Pinta, and the Vanishing Treasure, and The Ransom Note Blues. (And on a personal note, she is just as good a storyteller in person as she is in her books, and if there were any such thing as an editorial Best Dressed List, I have no doubt she would be on it.) Thanks for answering these questions, Jill!

Were you a writer or an editor first? I wrote stories my whole life--I still have one about a magical cat that I wrote when I was three--so I guess I'd have to say I was a writer first. But in terms of the kidlit world, I was an editor first. I started the first Alec book because I was around novels all day and wanted to see if I could write one from start to finish.

Who taught you how to edit? It's funny because editing doesn't seem to be a thing that's taught like calculus, say, or grammar or the alphabet. It seems to be more of a learn-by-osmosis process. In thinking about it, I probably first learned the skills that help me to edit as an undergrad English major at Columbia--picking out themes, plot devices, endowed objects, whatever it was that I pulled out of a story to use in an essay. Then it was probably Laura Geringer and Tamar Brazis, who I worked for in my first job as an editorial assistant, who taught me more. Tamar and I would sometimes sit and write a reader's report together, and through that I learned what types of things were important to focus on when putting thoughts together for an editor who would be writing an editorial letter. And then I'd read Laura's letters to authors and see which of Tamar and my points were included, what she'd added, how she worded her letters, etc.

After all of that, I got my MFA at the Vermont College of Fine Arts where the professors send the students what amounts to an editorial letter every month. From all of my mentors there--David Gifaldi, Sharon Darrow, Cynthia Leitich Smith and Marion Dane Bauer--I learned even more about editing--especially how important it is to tell authors the things they've done right instead of only talking about what can be improved. A lot of it, too, especially line editing, I think is instinctual.

What was the primary idea or value you took away from that education? I think the primary idea I took from all of that is that editing is just one person trying her hardest to help another person make a book the best in can be, and that there's no absolute way to do that--and also that the process can evolve and change.

A followup question about something you mentioned above: What is an "endowed object"? I've never heard that specific term before. Endowed objects (at least as I learned about them) are particular items that have an added layer of meaning. For example, a hat that's not just there to keep someone's head warm, but is also there as a reminder of a boy's mother because it's the last thing she knitted for him before she died. And then let's say that the boy is now homeless, that hat represents love and family and a sense of belonging. So the hat becomes a sort of shorthand for those feelings and is a touchstone for the boy. Often in a story with an endowed object, that object is part of the resolution. So in the story I've just invented, when that boy becomes close friends with a younger girl in the homeless shelter, he gives his hat to her at the end, when he finds out that his long lost aunt is going to adopt him. He no longer needs that reminder of love and security, but this girl does.

You did an MFA in  Writing for Children at Vermont College -- how did that change your editing?

Writing for Children at Vermont College -- how did that change your editing? My Vermont MFA changed my editing a lot--as I mentioned before, it helped teach me what was important to include in an editorial letter. But it also gave me more of a writer's vocabulary and a way to articulate my thoughts--after Vermont I was able to express the things I felt instinctively in a clearer, more concise way.

While every book and author need something different, of course, do you have a more or less standard editorial process? If so, could you describe it? I don't have a paint-by-numbers process, but I think more or less this is what I do: I email a copy of the manuscript I'm working on to whomever is assisting me on the project. Then I print the document and I start reading with a pen in my hand. I make comments in the margins about things I think are working really well or that I find confusing or illogical. Sometimes I ask questions or make exclamations about what's going on in the story. At the same time, I line-edit, cutting sentences, adding words, making notes about places that could use some fleshing out, etc. While I'm doing that, I have a document open on my computer and I jot notes there for my editorial letter--those are usually bigger picture things. I don't bother writing in paragraphs or even in full sentences--I just type in things like "fix love triangle. guy reads as creepy." or "look at screen play structure for plot" or whatever. Once I finish reading the manuscript I go back into any scenes that I've gained a new perspective on after reading the end of the story and re-line edit those. After that I turn my typed shorthand notes into the first draft of a letter. Then I flip through the marked up pages, adding smaller things that I feel are important enough to make it out of the margins.

Once that's finished, I talk to whomever is backing me up editorially on the project. We chat about the book, about our questions, about what we loved, etc., and then I go back into the editorial letter, tweak it, and add in any thoughts that emerged from the meeting. Sometimes I even incorporate large paragraphs of an assistant or intern's reader's report into my letter--telling the author that so-and-so came up with this point and I wholeheartedly agree. Then I read through my letter one last time and send it off to the author via e-mail. I follow that with a hard-copy of the letter and the scribbled-upon manuscript pages. I usually tell my authors to put the editorial letter in the freezer for at least three days and then give me a call or send me an e-mail if they have any questions or want to discuss anything further. Some letters are longer than others, and the content of the letter always depends on what a certain author's writing strengths are. I think I usually go through this process approximately three times on each book I edit (though of course some books need fewer rounds and some need more).

"The content of the letter always depends on what a certain author's writing strengths are" -- I agree absolutely. Could you talk a little about how you shape the content to suit those strengths? For instance, if an author's greatest strength was characterization, would you start from a characterization perspective, or would you talk in terms of plot instead because that's what needs more work? How do you make that judgment? You hit on exactly what I do in the second half of your question--if a writer has characterizations down, I focus on plot or dialogue or something else. And if someone is awesome at plot, I tend to spend more time talking about other aspects of the craft. As for how I make that judgment, it's usually pretty clear to me once I've read something. (Maybe that's the instinct part of the job?)

How would you define the editorial role in making a book? I think a book's editor has two main roles to play in the book-making process. First I think the editor is the book's in-house champion and guardian. From pitching the book to the publisher to introducing it to the sales and marketing groups at launch to stepping in when someone needs to dress up in a Pig costume to promote the book at BEA, I think the editor's job is to get across her passion for the project. Second, I think the editor is the book's creative guide. I think it's the editor's job to help the author realize his or her vision for the story as best as s/he can, to talk to the art director about the jacket and design, talk to marketing and sales folks about the title, and make sure the book comes together as a creative whole.

What are some common themes or ideas or motifs that run through the books you acquire? I've been thinking about that a lot recently, especially since I moved to Penguin--once I got here a lot of agents started asking me what defines me as an editor. This is what I've come up with in a nutshell: Most of the books I acquire are about empowerment. About kids who realize they're stronger, smarter and more capable than they thought they were or than society told them they were. That's a really important message to me--I don't think my books necessarily shout that message, but subtly, I think it's there in a lot of them. Empowerment in general--and actually female empowerment in specific. I love books that star strong women.

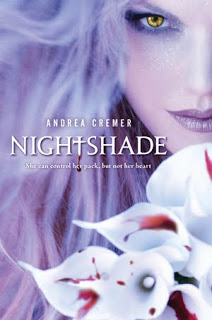

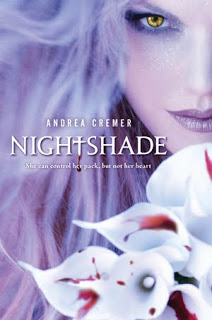

What book of yours has come out most recently? Could you tell me a little about it? Since I've only been at Penguin for about ten months, my first Penguin novel won't be out until

October, but I'll talk a little bit about that one. It's called NIGHTSHADE and is the first in a trilogy. The book is about a girl, Calla, who is the alpha female in a shape-shifting wolf pack. From birth she's known two things: She was born to serve the Keepers, and she was born to marry Ren LaRoche, the alpha male of a rival pack. But when she saves a human boy who was out hiking in the woods, she finds out some things about the Keepers that make her question her destiny. The book is really cinematic and tense and wonderful. I love the writing and the characters and the way Calla takes charge of her life. (There's that empowerment thing again...)

How many hours did you work in the past week? Probably about 60 (or maybe even more), but this was ALA week, so it's not a fair judge. I'd say I usually work about 45ish.

In an ideal world, with practicality being no object, what would you have done if you hadn't become a children's book editor? How does that interest or passion influence what you do now? I probably would've gotten a PhD in childhood studies, taught in a university and written academic books (and probably fiction too) about children and childhood and how the experience of grown up has changed through the decades. I'm fascinated by the sociology, psychology and development of children and the way those things relate to the books children read, the games they play, and what they get out of those activities. I think it's probably another side of the same passion that lead me to becoming a children's book editor (and writer). Instead of studying children, I'm helping to create books that (hopefully) will affect them in a good way. I think that's part of why I'm so interested in books that have a message of empowerment and equality.

How do your writerly and editorial brains work together? Do you turn off one when you're using the other? Or do they take turns, or work simultaneously? (Would you even separate them into two brains?) I wish I could turn the editorial one off once in a while! Unfortunately, they're not separate--they're just one unified brain. When I write, I have to force myself not to revise chapters over and over and over again before I move on. I'm getting better, though, at moving ahead, getting words on a page, and making notes on what I need to work through so I can go back to them later. (After writing that, it makes me wonder if my brain is an editor's brain that I'm forcing to write stories...hmmm.)

I've always been impressed by your writerly discipline -- that you do two pages per day, even on top of all your editorial work. How did you discover this process? What makes it work for you? Well, two pages a day was my grad school method and is still my "novel under contract" method, but I've been slacking a bit as far as productivity goes recently. I do love two pages a day though--I feel like it's a doable goal. It takes me about 30-40 minutes, which is an amount of time that is pretty easy to find. Plus it makes it so that my brain is always involved in the story. I learned about the idea of writing a set amount each day from Michael Stearns, a former Harper colleague and current agent, who I think read about it in an article (or something) on Graham Greene.

Both of the novels you've published thus far are mysteries. What attracts you to the mystery form? What sort of planning goes into a mystery for you, distinct from other genres?

Both of the novels you've published thus far are mysteries. What attracts you to the mystery form? What sort of planning goes into a mystery for you, distinct from other genres? I've always loved mysteries, from

Nate the Great on. And what I love about reading them is also what I love about writing them: they're a puzzle. I like putting them together so that the reader can solve the mystery along with the main character--feed information in different ways at different times. I plan a lot when I write a mystery, but honestly, I plan a lot when I write anything. With a mystery, I come up with the problem, the perp, the clues, and the red herrings in advance. Then I put them in an order that I think won't give the answer away and will keep people curious. After that, I figure out how many chapters I'll need to tell the story and write a one- or two-sentence summary of what happens in each chapter and which clue or red herring will be used. The nice thing is that once the chapter outline is done, I can zoom ahead with the writing.

As an editor, what are three pieces of advice you would give to beginning writers?

As an editor, what are three pieces of advice you would give to beginning writers? Hmm, okay: 1) This is a slow business, but everything will come together in the end, so try to be patient. 2) Make sure your expectations for your book and your publisher's expectations for the book are the same. 3) Don't forget to take a deep breath and enjoy the ride.

As a writer, what are three pieces of advice you would give to beginning writers?1) Don't be afraid to ask questions (to your agent or your editor). 2) Talk to the publicist assigned to your book to find out what you can do to help promote your book in a helpful (and not harmful) way. 3) Don't forget to take a deep breath and enjoy the ride.