“I begin with an idea and then it becomes something else.” — Picasso

"If you want to find, you must search. Rarely does a good idea interrupt you." — Jim Rohn

"You get ideas from daydreaming. You get ideas from being bored. You get ideas all the time. The only difference between writers and other people is we notice when we’re doing it." — Neil Gaiman

"The best way to have a good idea is to have a lot of ideas." — Linus Pauling

"If you are seeking creative ideas, go out walking. Angels whisper to a man when he goes for a walk." — Raymond Inman

“Ideas are like rabbits. You get a couple and learn how to handle them, and pretty soon you have a dozen.” — John Steinbeck

“That’s the great secret of creativity. You treat ideas like cats: you make them follow you.” — Ray Bradbury

"The question authors get asked more than any other is "Where do you get your ideas from?" And we all find a way of answering which we hope isn't arrogant or discouraging. What I usually say is ‘I don't know where they come from, but I know where they come to: they come to my desk, and if I'm not there, they go away again.’” — Philip Pullman

“Creative ideas flourish best in a shop which preserves some spirit of fun. Nobody is in business for fun, but that does not mean there cannot be fun in business.” — Leo Burnett

“First drafts are for learning what your novel or story is about. Revision is working with that knowledge to enlarge and enhance an idea, to re-form it.... The first draft of a book is the most uncertain—where you need guts, the ability to accept the imperfect until it is better.” —Bernard Malamud

“To get the right word in the right place is a rare achievement. To condense the diffused light of a page of thought into the luminous flash of a single sentence, is worthy to rank as a prize composition just by itself....Anybody can have ideas--the difficulty is to express them without squandering a quire of paper on an idea that ought to be reduced to one glittering paragraph.” — Mark Twain

“All words are pegs to hang ideas on.” — Henry Ward Beecher

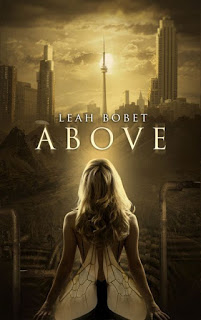

“A book is the only place in which you can examine a fragile thought without breaking it, or explore an explosive idea without fear it will go off in your face. It is one of the few havens remaining where a mind can get both provocation and privacy.” — Edward P. Morgan

"An idea that is not dangerous is unworthy of being called an idea at all." — Oscar Wilde

“Every man is a creature of the age in which he lives, and few are able to raise themselves above the ideas of the time.” —Voltaire

“When we want to infuse new ideas, to modify or better the habits and customs of a people, to breathe new vigor into its national traits, we must use the children as our vehicle; for little can be accomplished with adults.” — Maria Montessori

“We have a powerful potential in our youth, and we must have the courage to change old ideas and practices so that we may direct their power toward good ends.” — Mary McLeod Bethune

“Cautious, careful people always casting about to preserve their reputation or social standards never can bring about reform. Those who are really in earnest are willing to be anything or nothing in the world's estimation, and publicly and privately, in season and out, avow their sympathies with despised ideas and their advocates, and bear the consequences.” — Susan B. Anthony

“Our heritage and ideals, our code and standards — the things we live by and teach our children — are preserved or diminished by how freely we exchange ideas and feelings.” — Walt Disney

“We are not afraid to entrust the American people with unpleasant facts, foreign ideas, alien philosophies, and competitive values. For a nation that is afraid to let its people judge the truth and falsehood in an open market is a nation that is afraid of its people.” — John F. Kennedy

“Oh, would that my mind could let fall its dead ideas, as the tree does its withered leaves!” —Andre Gide

“A fixed idea is like the iron rod which sculptors put in their statues. It impales and sustains.” — Hippolyte Taine

“Apologists for a religion often point to the shift that goes on in scientific ideas and materials as evidence of the unreliability of science as a mode of knowledge. They often seem peculiarly elated by the great, almost revolutionary, change in fundamental physical conceptions that has taken place in science during the present generation. Even if the alleged unreliability were as great as they assume (or even greater), the question would remain: Have we any other recourse for knowledge? But in fact they miss the point. Science is not constituted by any particular body of subject matter. It is constituted by a method, a method of changing beliefs by means of tested inquiry.... Scientific method is adverse not only to dogma but to doctrine as well.... The scientific-religious conflict ultimately is a conflict between allegiance to this method and allegiance to even an irreducible minimum of belief so fixed in advance that it can never be modified.” — John Dewey

“A belief is not an idea held by the mind, it is an idea that holds the mind.” — Elly Roselle

“To die for an idea; it is unquestionably noble. But how much nobler it would be if men died for ideas that were true.” — H.L. Mencken

“The man who strikes first admits that his ideas have given out.” — Chinese proverb

“We should have a great many fewer disputes in the world if words were taken for what they are, the signs of our ideas, and not for things themselves.” — John Locke

"Ideas are far more powerful than guns. We don't allow our enemies to have guns, why should we allow them to have ideas?" — Joseph Stalin

"Beware of people carrying ideas. Beware of ideas carrying people." — Barbara Harrison

“What matters is not the idea a man holds, but the depth at which he holds it.” — Ezra Pound

“The only force that can overcome an idea and a faith is another and better idea and faith, positively and fearlessly upheld.” — Dorothy Thompson

"If you want to find, you must search. Rarely does a good idea interrupt you." — Jim Rohn

"You get ideas from daydreaming. You get ideas from being bored. You get ideas all the time. The only difference between writers and other people is we notice when we’re doing it." — Neil Gaiman

"The best way to have a good idea is to have a lot of ideas." — Linus Pauling

"If you are seeking creative ideas, go out walking. Angels whisper to a man when he goes for a walk." — Raymond Inman

“Ideas are like rabbits. You get a couple and learn how to handle them, and pretty soon you have a dozen.” — John Steinbeck

“That’s the great secret of creativity. You treat ideas like cats: you make them follow you.” — Ray Bradbury

"The question authors get asked more than any other is "Where do you get your ideas from?" And we all find a way of answering which we hope isn't arrogant or discouraging. What I usually say is ‘I don't know where they come from, but I know where they come to: they come to my desk, and if I'm not there, they go away again.’” — Philip Pullman

“Creative ideas flourish best in a shop which preserves some spirit of fun. Nobody is in business for fun, but that does not mean there cannot be fun in business.” — Leo Burnett

“First drafts are for learning what your novel or story is about. Revision is working with that knowledge to enlarge and enhance an idea, to re-form it.... The first draft of a book is the most uncertain—where you need guts, the ability to accept the imperfect until it is better.” —Bernard Malamud

“To get the right word in the right place is a rare achievement. To condense the diffused light of a page of thought into the luminous flash of a single sentence, is worthy to rank as a prize composition just by itself....Anybody can have ideas--the difficulty is to express them without squandering a quire of paper on an idea that ought to be reduced to one glittering paragraph.” — Mark Twain

“All words are pegs to hang ideas on.” — Henry Ward Beecher

“A book is the only place in which you can examine a fragile thought without breaking it, or explore an explosive idea without fear it will go off in your face. It is one of the few havens remaining where a mind can get both provocation and privacy.” — Edward P. Morgan

"An idea that is not dangerous is unworthy of being called an idea at all." — Oscar Wilde

“Every man is a creature of the age in which he lives, and few are able to raise themselves above the ideas of the time.” —Voltaire

“When we want to infuse new ideas, to modify or better the habits and customs of a people, to breathe new vigor into its national traits, we must use the children as our vehicle; for little can be accomplished with adults.” — Maria Montessori

“We have a powerful potential in our youth, and we must have the courage to change old ideas and practices so that we may direct their power toward good ends.” — Mary McLeod Bethune

“Cautious, careful people always casting about to preserve their reputation or social standards never can bring about reform. Those who are really in earnest are willing to be anything or nothing in the world's estimation, and publicly and privately, in season and out, avow their sympathies with despised ideas and their advocates, and bear the consequences.” — Susan B. Anthony

“Our heritage and ideals, our code and standards — the things we live by and teach our children — are preserved or diminished by how freely we exchange ideas and feelings.” — Walt Disney

“We are not afraid to entrust the American people with unpleasant facts, foreign ideas, alien philosophies, and competitive values. For a nation that is afraid to let its people judge the truth and falsehood in an open market is a nation that is afraid of its people.” — John F. Kennedy

“Oh, would that my mind could let fall its dead ideas, as the tree does its withered leaves!” —Andre Gide

“A fixed idea is like the iron rod which sculptors put in their statues. It impales and sustains.” — Hippolyte Taine

“Apologists for a religion often point to the shift that goes on in scientific ideas and materials as evidence of the unreliability of science as a mode of knowledge. They often seem peculiarly elated by the great, almost revolutionary, change in fundamental physical conceptions that has taken place in science during the present generation. Even if the alleged unreliability were as great as they assume (or even greater), the question would remain: Have we any other recourse for knowledge? But in fact they miss the point. Science is not constituted by any particular body of subject matter. It is constituted by a method, a method of changing beliefs by means of tested inquiry.... Scientific method is adverse not only to dogma but to doctrine as well.... The scientific-religious conflict ultimately is a conflict between allegiance to this method and allegiance to even an irreducible minimum of belief so fixed in advance that it can never be modified.” — John Dewey

“A belief is not an idea held by the mind, it is an idea that holds the mind.” — Elly Roselle

“To die for an idea; it is unquestionably noble. But how much nobler it would be if men died for ideas that were true.” — H.L. Mencken

“The man who strikes first admits that his ideas have given out.” — Chinese proverb

“We should have a great many fewer disputes in the world if words were taken for what they are, the signs of our ideas, and not for things themselves.” — John Locke

"Ideas are far more powerful than guns. We don't allow our enemies to have guns, why should we allow them to have ideas?" — Joseph Stalin

"Beware of people carrying ideas. Beware of ideas carrying people." — Barbara Harrison

“What matters is not the idea a man holds, but the depth at which he holds it.” — Ezra Pound

“The only force that can overcome an idea and a faith is another and better idea and faith, positively and fearlessly upheld.” — Dorothy Thompson